Brazil is home to the largest community of descendants of Japanese people abroad

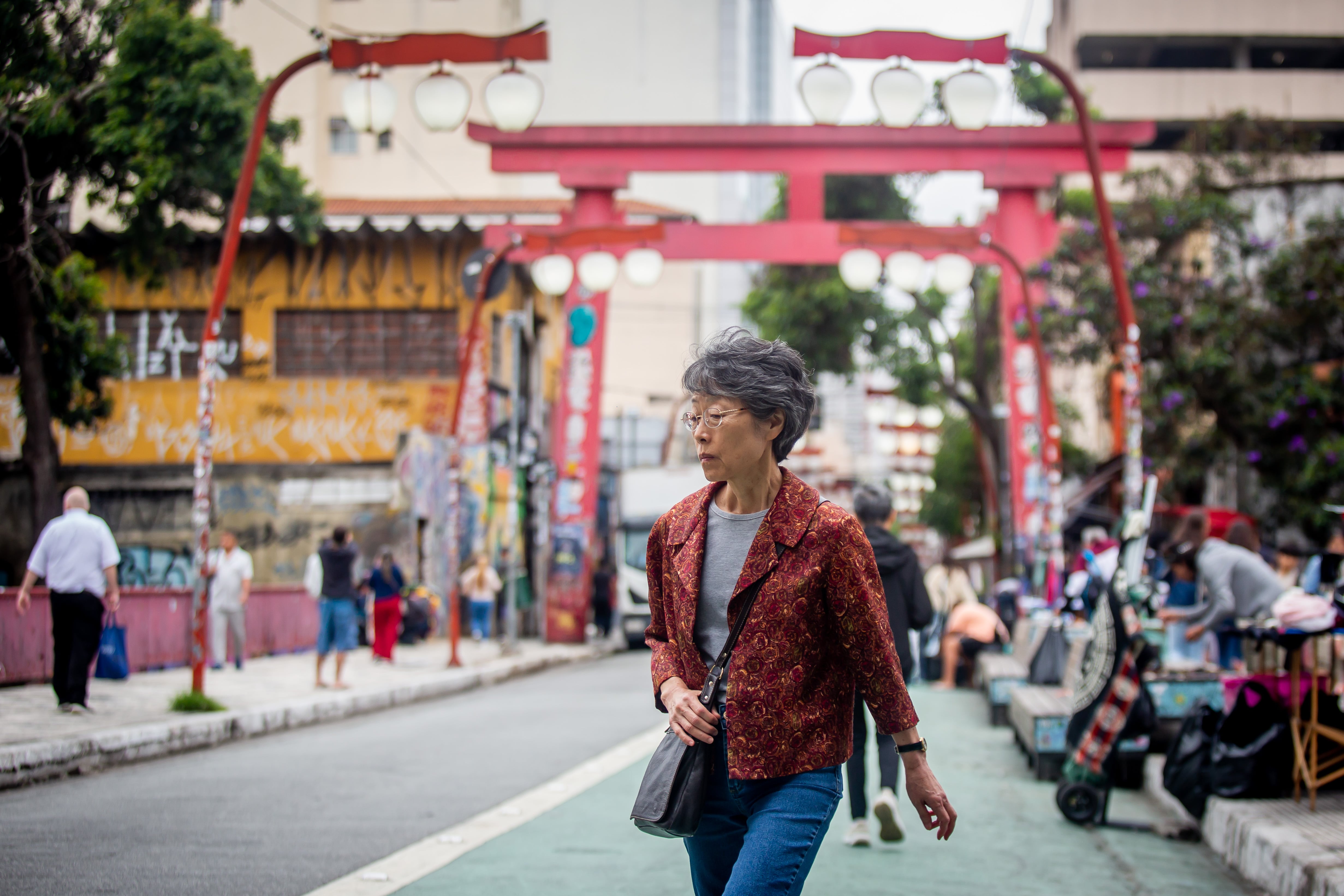

The 50-year-old businesswoman Andrea Terumi Nakagaito walks briskly through Liberdade, a neighborhood in São Paulo. There, elderly women carefully select vegetables, while sushi and chopsticks reign supreme. The most authentic taverns hold onto a customer’s sake bottle until their next visit. And, when you look up, a gigantic mural of Mount Fuji appears. Welcome to the most Japanese corner of Brazil.

Three of Terumi Nakagaito’s four grandparents arrived from the Land of the Rising Sun at the beginning of the 20th century. They came here through organized immigration programs: most came to work on coffee plantations in the interior of São Paulo. However, some were sent to settle remote corners of the Amazon.

The Japanese-Brazilians are descendants of impoverished pioneers who embarked for the unknown with the dream of prospering. They make up the largest Japanese community abroad, numbering between one and two million Brazilians, according to various sources. They embody the intimate historical relationship between two cultures on opposite sides of the world: a gregarious nature, paired with extreme shyness; the boisterousness of samba, alongside the calm of calligraphy.

With the abolition of slavery in 1888, Brazil turned to the world in search of labor, in order to continue the process of nation-building. At the same time, Brazilian authorities attempted to whiten the population, in line with the racist and misguided science of the era.

For decades, the Japanese community remained extremely closed, the most enigmatic among newcomers. Then, Japan’s defeat in World War II brought about a seismic shift. It shattered any dreams of returning. And, in their adopted homeland, mistrust of Japanese people intensified. During the war, the authorities interned them in camps (along with Italians and Germans).

After Tokyo’s surrender, a horrific event tore the Japanese-Brazilian community apart. A fanatical nationalist organization, Shindo Renmei, murdered around 20 of their compatriots, accusing them of being traitors because they had recognized the Allied victory. With Japanese newspapers banned in Brazil, the gang resorted to violence as part of a massive disinformation campaign, in order to convince their followers that Japan was victorious, not defeated.

Thousands of Japanese-Brazilians made the opposite journey in the 1990s. They emigrated to Japan, which saw them as cheap labor that would contaminate the island nation’s precious culture less than other foreigners.

Terumi Nakagaito and her family settled in Toyota. “There, if I didn’t open my mouth, I was Japanese. But when I spoke, it was obvious that I was Brazilian,” she explained, one recent morning in front of the Japão-Liberdade subway station.

From her long time in Japan, she misses the safety, the quality of education and the high standard of living. But she also remembers bitter moments: “The older generation considered us to be traitors, because they believed that our grandparents had fled the war.”

Many among the Japanese-Brazilians have felt like they were in limbo between disparate worlds. They were misunderstood: too Japanese in their homeland and too Brazilian in the country of their ancestors.

Only from the 1970s onward did they follow in the footsteps of other large immigrant communities – Portuguese, Italian, Spanish, German – and begin to mix with Brazilians from other cultures. And, along the way, many of them prospered. In two generations, they made a great leap in social class. This is well illustrated by the family of 74-year-old Ivonne Kawano, who stops only briefly to speak with EL PAÍS. She has plans to have lunch with her son and is running late. He’s a doctor – a very common profession among Japanese-Brazilians in São Paulo. His mother ran a beauty salon. And his grandparents, like so many others, earned a living as day laborers in the coffee industry.

Brazilian passports are among the most sought-after on the black market. This is because anyone can look Brazilian - even Kim Jong-un, the North Korean dictator. When he was a student at an elite school in Switzerland (and a basketball enthusiast), Kim traveled with a Brazilian passport that was obtained fraudulently. Alongside his real photo was a false identity: Josef Pwag, born in São Paulo in 1983. He was passing himself off as Japanese-Brazilian, a compatriot of Pelé and Gisele Bündchen.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

¿Por qué estás viendo esto?

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.

Comments

No comments yet.

Log in to leave a comment.